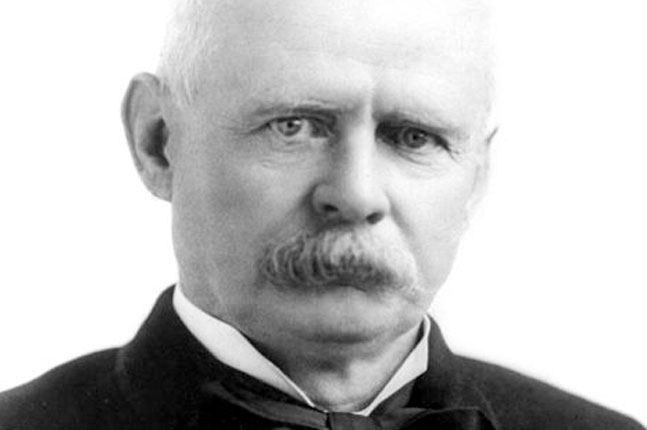

Adlai Ewing Stevenson served as the 23rd Vice President of the United States (1893–1897). Previously, he served as a Congressman from Illinois in the late 1870s and early 1880s. After his subsequent appointment as Assistant Postmaster General of the United States during Grover Cleveland’s first administration (1885–1889), he fired many Republican postal workers and replaced them with Southern Democrats. This earned him the enmity of the Republican-controlled Congress, but made him a favorite as Grover Cleveland’s running mate in 1892, and he duly became 23rd Vice President of the United States.

Stevenson attended Illinois Wesleyan University at Bloomington and ultimately graduated from Centre College, in Danville, Kentucky; at the latter he was a part of Phi Delta Theta.

In 1892, when the Democrats chose Cleveland once again as their standard bearer, they appeased party regulars by the nomination of Stevenson, “headsman of the post-office,” for vice president. As a supporter of using greenbacks and free silver to inflate the currency and alleviate economic distress in the rural districts, Stevenson balanced the ticket headed by Cleveland, the hard-money, gold-standard supporter. The winning Cleveland-Stevenson ticket carried Illinois, although not Stevenson’s home district.

Adlai Stevenson enjoyed his role as vice president, presiding over the U.S. Senate, “the most august legislative assembly known to men.” He won praise for ruling in a dignified, nonpartisan manner. In personal appearance he stood six feet tall and was “of fine personal bearing and uniformly courteous to all.” Although he was often a guest at the White House, Stevenson admitted that he was less an adviser to the president than “the neighbor to his counsels.” He credited the President with being “courteous at all times” but noted that “no guards were necessary to the preservation of his dignity. No one would have thought of undue familiarity.” For his part, President Cleveland snorted that the Vice President had surrounded himself with a coterie of free-silver men dubbed the “Stevenson cabinet.” The president even mused that the economy had gotten so bad and the Democratic party so divided that “the logical thing for me to do … was to resign and hand the Executive branch to Mr. Stevenson,” joking that he would try to get his friends jobs in Stevenson’s new cabinet.